Decades of war, state fragility, and the interplay of local, regional, and global actors have made Afghanistan a focal point for armed/militant groups. These groups operate under varying ideological, political, and strategic objectives, often using violence to achieve their goals. While some claim to represent national or religious causes, their actions, ranging from targeted attacks against specific ethnic and religious communities to large-scale violence aimed at instilling fear, have resulted in thousands of civilian casualties and widespread displacement over the past 25 years.

Despite the Taliban’s return to power, international perspectives on their status remain divided. The U.S. has not officially designated them as a terrorist organization, yet intelligence assessments from U.S. agencies, the Department of Defense, and the United Nations indicate longstanding ties between the Taliban and groups classified as terrorist organizations by the U.S. and other countries. The 2020 U.S.-Taliban agreement, which facilitated the U.S. withdrawal, included provisions requiring the Taliban to prevent such groups from using Afghan territory for operations. However, given the historical and operational ties between these actors, it remains unclear how effectively this commitment is being enforced. Meanwhile, the U.S. and NATO continue intelligence-gathering operations and, if necessary, airstrikes against perceived terrorist threats in Afghanistan. The Taliban, for their part, have denied allegations of harboring these groups, but reports suggest that certain armed factions continue to operate freely, benefiting from the broader security environment under Taliban rule.

The extent of Afghanistan’s militant landscape was formally documented in March 2017, when the Afghan National Police (ANP) submitted a comprehensive list of active militant groups to Interpol, marking a significant effort to illustrate the scale and complexity of insurgent activity. Intelligence reports at the time highlighted extensive cross-border support, with 32 known terrorist training centers and 85 senior commanders allegedly operating from across the border. The number of foreign insurgents fluctuated between 50,000 and 75,000, demonstrating the fluid nature of recruitment and mobilization. Additionally, 168 armed groups, ranging from localized cells to transnational networks, were actively engaged in insurgency, with an estimated 60,000 to 100,000 fighters involved.

The Interpol report underscored the deeply interconnected nature of militant networks in Afghanistan, where foreign-backed insurgencies, global jihadist movements, and local armed factions have collectively contributed to prolonged instability. These findings highlighted Afghanistan’s role as part of a wider regional and global security challenge, requiring sustained and coordinated counterterrorism strategies. While international definitions of terrorism vary, these groups continue to shape Afghanistan’s security landscape, making a thorough understanding of their activities and affiliations crucial for assessing the country’s evolving conflict dynamics. Although the political and security landscape of Afghanistan has changed significantly since 2017, several major and minor armed groups have operated in the country, with some continuing to do so.

Major groups

The Taliban

The Taliban, as they rule Afghanistan today, were once divided into competing factions. The most prominent were the Quetta Shura faction, led by Mullah Mansour and later Mullah Hibatullah Akhundzada, and the breakaway faction led by Mullah Rasul. The Quetta Shura Taliban was the dominant force, commanding an estimated 35,000 fighters and maintaining strong cross-border networks. Its leadership included key figures such as Sirajuddin Haqqani, head of the Haqqani Network, and Mullah Mohammad Yaqoob, son of Mullah Omar. This faction played a decisive role in the Taliban’s military campaign, ultimately leading to their takeover of Afghanistan in August 2021. In contrast, the Mullah Rasul faction emerged as a breakaway group, with an estimated 15,000 to 25,000 fighters operating across Herat, Farah, Badghis, Faryab, Helmand, Zabul, Ghazni, and Paktya provinces. While this faction initially sought to challenge the leadership of the Quetta Shura, it gradually weakened over time. Unlike the main Taliban leadership, Mullah Rasul had shown some willingness to engage in negotiations with the former Afghan government. Despite these past divisions, the Quetta Shura faction ultimately consolidated power, and today, its leadership under Mullah Hibatullah Akhundzada, Sirajuddin Haqqani, and Mullah Yaqoob governs Afghanistan. The internal rivalries that once defined the insurgency have been largely subdued; however, the Taliban today face even greater threats, mostly internal difference over women’s rights such as education and work and reconciliation with and incorporation of other sectors of the Afghan population.

Al-Qaeda’s core leadership

Al-Qaeda’s core leadership has remained a key target for the United States since the September 11, 2001 attacks, with successive operations aimed at eliminating its senior figures. Among them was Ayman al-Zawahiri, the former leader, along with his deputies and advisors who have shaped the group’s strategy and maintained its operational networks. Despite sustained counterterrorism efforts, Al-Qaeda’s leadership has shown resilience, adapting to changing battlefield dynamics and leveraging its long-standing alliances. The Taliban-Al-Qaeda relationship, which dates back to the 1990s when the Taliban first provided sanctuary to Osama bin Laden, has not only endured but, according to United Nations assessments, has strengthened over the past two decades. The two groups have fought side by side against foreign forces, and the intermarriage of members has further solidified their ties, making their alliance more than just strategic—it is also deeply personal. Even after years of counterterrorism operations, senior Al-Qaeda leaders continue to find refuge in Afghanistan and Pakistan’s border regions. While such strikes have weakened Al-Qaeda’s centralized command, they have not eradicated its presence in the region. The group continues to operate through decentralized cells, maintaining influence through its affiliates and benefitting from the Taliban’s rule in Afghanistan.

Al-Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent (AQIS)

In 2014, former Al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri announced the formation of Al-Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent (AQIS) as a regional extension of the group, aiming to strengthen ties with local factions across South Asia. While AQIS operates under Al-Qaeda’s ideological umbrella, it differs in structure and leadership. Unlike Al-Qaeda’s core leadership, which has historically been Arab-dominated, AQIS was designed with local leadership to integrate more effectively into South Asian militant landscapes. AQIS’s founding leader, Asim Umar, was an Indian national who operated in Afghanistan under Taliban protection, according to intelligence reports. He was killed on September 23, 2019, in a joint U.S.-Afghan military operation in Helmand province. His influence extended beyond Afghanistan, particularly into Pakistan, where AQIS has maintained active cells and operational networks. Although AQIS forces have largely merged with the Taliban, their objectives extend beyond Afghanistan, with documented attacks in Pakistan and Bangladesh, often targeting security forces and activists. The U.S. Department of Defense has previously assessed AQIS as a threat to American forces in Afghanistan, highlighting its regional ambitions and operational reach. The group continues to exploit Afghanistan’s security environment, benefiting from the broader militant ecosystem that has persisted despite years of counterterrorism efforts.

Ansarullah of Tajikistan (Tajik Taliban)

Since the Taliban’s return to power in Afghanistan, multiple reports have documented the presence of foreign militant groups in the country, with Jamaat Ansarullah of Tajikistan being one of the most frequently highlighted. The group was founded in 2006 by Amriddin Tabarov (Tabari), also known as Mullah Amriddin, who was later killed by Afghan government forces in 2016. Following a terrorist attack in Khujand, Tajikistan, the group was officially designated as a terrorist organization, though some observers refer to it as the “Tajik Taliban” due to its operational and ideological alignment with the Afghan Taliban. However, the group itself has not publicly commented on this designation. Since the Taliban’s takeover, the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) and its monitoring bodies have repeatedly reported on Jamaat Ansarullah’s activities in Afghanistan, emphasizing its close relationship with the Taliban. According to these reports, the group has established training camps in Khost province, allegedly under the supervision of Al-Qaeda trainers, and a military center in Takhar province to train fighters from Central Asia. Further claims suggest that Jamaat Ansarullah has set up a special unit in Kunduz province tasked with border infiltration. The reports also allege that the Taliban has stationed a suicide unit in Badakhshan province, which includes fighters from Jamaat Ansarullah and has been deployed against opposition resistance forces. The group’s increasing role in northern Afghanistan has raised security tensions in Tajikistan and other Central Asian states, prompting fears that Afghanistan could once again become a launchpad for regional insurgencies.

Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan (IRPT)

The Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan (IRPT) was once Tajikistan’s main Islamist political party, playing a key role in the Tajik Civil War (1992–1997) before being banned in 2015. While it was primarily a political movement, its suppression led some members to seek refuge in Afghanistan, where the party historically had ties with Afghan political and militant groups. During the civil war, Afghanistan served as a safe haven for IRPT fighters, and after the party’s dissolution, some former members aligned with Jamaat Ansarullah, a Tajik militant group active in northern Afghanistan. Though IRPT itself does not engage in armed insurgency, its past connections and the presence of Tajik Islamist groups in Afghanistan remain relevant to regional security concerns.

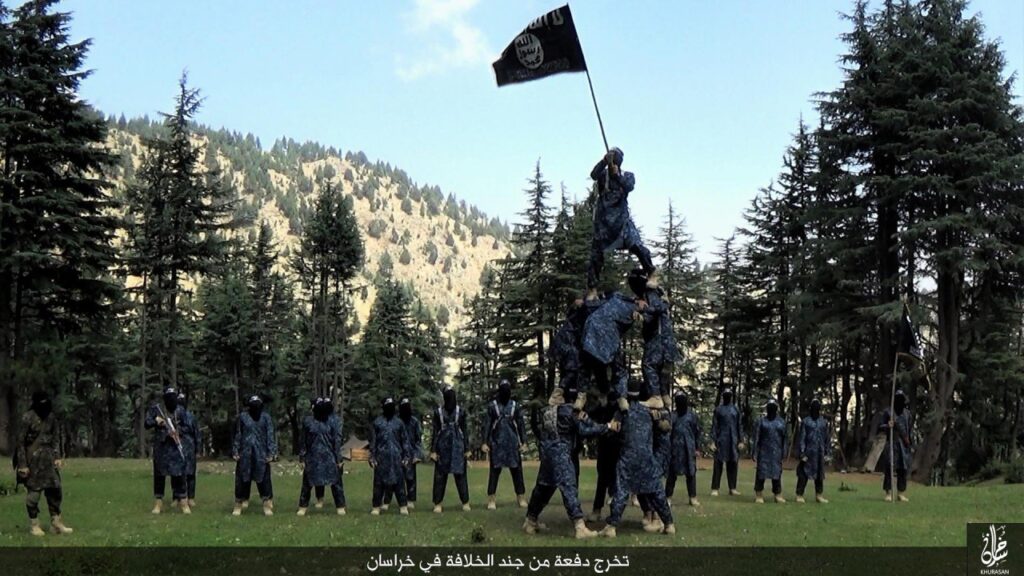

Islamic State – Khorasan Province (ISIS-K)

In 2014, the Islamic State (ISIS) formally announced the establishment of its Khorasan Province branch (ISIS-K) in Afghanistan, positioning itself as a regional offshoot of the broader ISIS network. Initially, ISIS-K consolidated its presence in eastern Afghanistan, particularly in Nangarhar province, near the Pakistan-Afghanistan border. Many of its early members were former fighters from Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) who had fled Pakistan following military operations against them. ISIS-K has been responsible for some of the deadliest attacks on civilians, frequently targeting Shiite communities. Notable attacks include the bombing of a girls’ school in Kabul in 2021 and the attack on a maternity hospital in Kabul in 2020, both of which underscored the group’s brutal sectarian violence. By late 2018, U.S. forces and the Afghan Taliban separately launched offensives against ISIS-K, successfully driving the group from many of its strongholds in eastern and northern Afghanistan. However, rather than being eliminated, ISIS-K adapted to these setbacks. Taliban and ISIS-K have been rivals, engaging in multiple battles over territorial control.

The Haqqani Network

The Haqqani Network is a semi-autonomous faction within the Taliban, founded by Jalaluddin Haqqani, a prominent Mujahideen commander during the Soviet-Afghan war. Originally operating as an independent militant group, it became an integral but distinct branch of the Taliban when Jalaluddin Haqqani formally aligned with the movement. Over the years, the network has functioned as a family-led organization, maintaining its own leadership structure, funding sources, and operational strategies while remaining deeply embedded within the Taliban hierarchy. After the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, the Haqqani Network played a pivotal role in insurgent operations, carrying out some of the deadliest and most sophisticated attacks in Afghanistan. The network has been linked to Al-Qaeda, a relationship that, according to United Nations reports, has grown stronger under Sirajuddin Haqqani, who now serves as both the leader of the Haqqani Network and the Taliban’s minister of interior. The Haqqani Network has long been accused of having ties to Pakistan’s intelligence services (ISI), though Pakistan denies these allegations. The U.S. has designated the Haqqani Network as a terrorist organization, and multiple U.S. air and ground operations have targeted its leadership, killing four of Jalaluddin Haqqani’s sons. Despite multiple assassination attempts, Sirajuddin Haqqani remains a key Taliban figure, now occupying a senior leadership position within Afghanistan’s current Taliban government. The Haqqani Network’s influence within the Taliban has only grown since the Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan, raising concerns about its role in the country’s security, governance, and relations with transnational militant organizations.

Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP)

Commonly known as the Pakistani Taliban, Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) was formed with the primary objective of fighting against the Pakistani government. While distinct from the Afghan Taliban, TTP has historically maintained strong ties with its Afghan counterpart, with fighters from both groups having fought alongside each other against Afghan security forces and civilians in the past two decades. TTP operates not as a single, centralized organization but rather as an umbrella group comprising various extremist factions united by their opposition to the Pakistani state. The group suffered internal divisions following the 2013 U.S. drone strike that killed its leader, Hakimullah Mehsud, leading to defections, including some members joining ISIS in Afghanistan. Subsequent Pakistani military operations further displaced TTP fighters, pushing many of them from northern Pakistan into eastern Afghanistan, where they reorganized and continued operations. In the past two years, intelligence assessments from both U.S. and United Nations sources indicate that several breakaway Islamist factions have rejoined TTP, strengthening the group’s operational capacity. Some of these factions also have links to Al-Qaeda, reinforcing concerns about TTP’s role in the broader jihadist landscape. With Afghanistan now under Taliban rule, the future trajectory of TTP remains uncertain, particularly regarding its relationship with the Afghan Taliban and its cross-border activities.

Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU)

The Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) has been designated as a terrorist organization by the United States for over two decades and was once a close ally of Al-Qaeda. The group initially consisted of fighters from the Tajikistan civil war in the 1990s and later expanded its operations across Central Asia. Historically, IMU maintained strong ties with the Taliban, benefiting from their support to carry out attacks in Central Asian countries. However, after the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, IMU shifted its focus to conducting operations within Afghanistan and Pakistan. The group remained active in insurgent activities, frequently collaborating with other militant factions. According to United Nations assessments, IMU has, in recent years, come under the Taliban’s control and now operates primarily in northern Afghanistan. While it once had broader regional ambitions, the group’s current activities appear to be aligned with Taliban objectives, further entrenching its presence in Afghanistan’s evolving security landscape.

East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM) / Turkistan Islamic Party (TIP)

The East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM), also known as the Turkistan Islamic Party (TIP), seeks to establish an independent Islamic state for Uyghurs in China’s Xinjiang region and other Turkic-speaking communities across Central Asia. Historically, the group has been associated with global jihadist networks, maintaining ties with both the Taliban and Al-Qaeda. Before the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, ETIM was designated as a terrorist organization by the United States, largely due to its connections with the Taliban. However, in 2020, the U.S. removed ETIM from its terrorist list, citing a lack of credible intelligence on its activities in recent years. This decision was met with skepticism, as United Nations assessments continue to suggest that ETIM remains operational, with hundreds of fighters still present in northern Afghanistan. The group is also believed to move its fighters between Afghanistan and Syria, where it has maintained an active presence in Idlib province alongside other transnational jihadist groups. ETIM was notably involved in the Syrian civil war, with images and battlefield reports confirming its participation against the Syrian government. While its primary objective remains focused on China’s Xinjiang region, its engagement in Syria underscores its broader transnational ambitions, positioning it as a regional and global security concern.

Minor groups

Harakat-ul-Jihad-al-Islami (HUJI)

Founded in 1984 during the Soviet-Afghan war by Fazlur Rahman Khalil and Qari Saifullah Akhtar, Harakat-ul-Jihad-al-Islami (HUJI) has been involved in militant activities across multiple regions. The group has specifically targeted the United States, Israel, Bangladesh, and New Zealand. While HUJI’s main base is in Palestine, it has had a small presence in Afghanistan, with reports indicating that a 15-member unit was involved in fighting against U.S. forces. The group’s influence has been diminished in Afghanistan. Although it maintains ideological affiliations with other larger networks, its operational activities have been minimal in recent years.

Hezb-e Islami (HIG) and Hezb-e Islami Khalis

Hezb-e Islami Afghanistan, once a major militant faction, aligned itself with the former Afghan government, shifting away from active insurgency. A splinter group, Hezb-e Islami Khalis, largely integrated into the Afghan political structure as well. However, Anwarul Haq Khalis, son of Mawlawi Khalis, pledged allegiance to Mullah Hibatullah Akhundzada, bringing 1,000 fighters under Taliban command. While much of the group joined the government, this faction’s integration into the Taliban ranks reflects the complex nature of Afghanistan’s armed movements, where alliances continue to shift.

Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT)

Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT) is one of the most dangerous Pakistani and Kashmiri militant groups, reportedly operating with the backing of Pakistan’s intelligence agency (ISI). Led by Hafiz Muhammad Saeed, LeT maintained an active presence in Afghanistan, engaging in insurgent operations. The group was allegedly responsible for the attack on Kabul’s 400-bed military hospital, demonstrating its operational reach beyond Kashmir and Pakistan.

Lashkar-e-Islam

Lashkar-e-Islam, originally based in Khyber Agency, was founded by Mufti Munir Shakir and is currently led by Mangal Bagh. Unlike LeT, this group has pledged allegiance to ISIS and operates against both the Pakistani and Afghan governments. Its affiliation with ISIS reflects its shift toward a more global jihadist agenda, making it distinct from other regional insurgent groups.

Indian terrorist group: Abdul Azim and Shaheed Brigades

Little information is publicly available on the Indian terrorist group referred to as Abdul Azim and Shaheed Brigades, but its presence suggests the existence of militant factions operating beyond Afghanistan’s immediate conflict zones, with potential transnational linkages.

Jaish-e-Mohammad (JeM)

Jaish-e-Mohammad (JeM) is a Pakistan-based militant group, originally formed as a Kashmiri separatist organization but now actively involved in militant operations beyond Kashmir, including in Afghanistan. Led by Maulana Masood Azhar, JeM has been accused of conducting attacks against former Afghan government forces while maintaining its strong presence in Kashmir. Despite its initial focus on India-administered Kashmir, JeM’s activities in Afghanistan highlight its expanding operational reach, aligning it with broader regional jihadist movements. Its involvement in Afghanistan underscores the complex interplay between militant groups, cross-border insurgencies, and shifting alliances in South Asia’s security landscape.

Islamic Emirate of Waziristan

The Islamic Emirate of Waziristan was a Pakistani Taliban faction that previously operated under the leadership of the Haqqani Network. It emerged as a semi-autonomous militant entity in Pakistan’s tribal areas, particularly in North and South Waziristan, serving as a key hub for insurgent activities and cross-border attacks. Although the group was primarily composed of Pakistani Taliban fighters, its alignment with the Haqqani Network reinforced its strategic role in the broader insurgency. Over time, its presence diminished as Pakistan intensified military operations in the region, leading many of its fighters to relocate to Afghanistan or merge with other militant factions.

Sipah-e-Sahaba Pakistan (SSP)

Sipah-e-Sahaba Pakistan (SSP) is a Pakistani Wahhabi militant group that emerged as a sectarian organization, primarily targeting Shia communities. Originally a splinter faction of Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam Pakistan (JUI), it was founded by Haqnawaz Jhangvi following the Soviet military intervention in Afghanistan. SSP has been linked to violent sectarian attacks, particularly in Pakistan, and has a reported membership of around 100,000 fighters. The group is politically aligned with Lashkar-e-Jhangvi (LeJ), which serves as its military wing, carrying out some of the deadliest sectarian bombings—particularly during Muharram and on Ashura, the holiest day for Shia Muslims. Although SSP primarily operates in Pakistan, its financial backing reportedly comes from Saudi Arabia and Gulf states, which have historically supported various ideological and militant movements in the region. The group’s activities have exacerbated sectarian violence across South Asia, making it one of the most notorious extremist organizations in the region.

Tehrik-e-Nifaz-e-Shariat-e-Mohammadi (TNSM)

Tehrik-e-Nifaz-e-Shariat-e-Mohammadi (TNSM) is a militant movement that originally emerged in Swat, Pakistan, advocating for the strict implementation of Sharia law. The group was known for its opposition to the Pakistani government, engaging in armed confrontations to enforce its interpretation of Islamic governance. Although once a major insurgent force, TNSM has weakened in recent years. Its leader, Sufi Muhammad, eventually signed a peace agreement with the Pakistani government, signaling a shift away from direct militant opposition. However, despite this political reconciliation, elements of the group remained active in Afghanistan, particularly in Chitral and Warduj.

Ittehad-e-Jihad-e-Islami (Islamic Jihad Union – IJU)

Ittehad-e-Jihad-e-Islami (IJU) is a militant group that claims to control large portions of the Afghanistan-Tajikistan border and maintains ties with both the Taliban and Al-Qaeda. Reports suggest that significant areas of Imam Sahib and Dasht-e-Archi districts in Kunduz were/are under the joint control of this group and allied factions. While its primary focus appears to be in northern Afghanistan, IJU is also active in Tajikistan, where it seeks to challenge Russia’s military presence along the border. Beyond Central Asia, IJU reportedly has operational links in Europe, further underlining its international network and ambitions. Its activities reflect the wider militant landscape in Afghanistan, where various armed factions exploit the region’s instability to pursue both local and cross-border objectives.

Lashkar-e-Jhangvi (LeJ)

Lashkar-e-Jhangvi (LeJ) is a sectarian militant group founded by Haq Nawaz Jhangvi and Malik Ishaq in 1996, after splitting from Sipah-e-Sahaba Pakistan (SSP). The group is known for its extreme anti-Shia ideology and has been involved in numerous sectarian attacks in Afghanistan and Pakistan. With an estimated 200 fighters, LeJ has actively targeted Shia communities in Afghanistan, particularly in Kabul and Mazar-e-Sharif. The Dehmazang bombing against the Enlightenment Movement was attributed to LeJ, underscoring its role in high-profile sectarian violence. Led by Qari Muhammad Yasin, LeJ has used Waziristan as its main base and has been responsible for suicide bombings and attacks during Ashura, a key Shia religious observance. Its deep-rooted sectarian agenda and operational alliances with regional jihadist groups, including the Taliban and Al-Qaeda, make it a persistent security concern in the region.

Harakat-ul-Mujahideen (HuM)

Harakat-ul-Mujahideen (HuM) is a militant group with historical ties to Al-Qaeda, operating under the alias “Ansar al-Ummah.” With an estimated 8,000 fighters, the group is/was primarily active in eastern Afghanistan, where it maintained a presence despite counterterrorism efforts. HuM operates freely in Pakistan, reportedly with the approval of certain state institutions, including Pakistan’s intelligence services (ISI). HuM has long been focused on Kashmir, seeking its integration into Pakistan through armed struggle. However, its activities in Afghanistan and its hostility toward U.S. interests make it a security threat beyond the Kashmir conflict, adding to the complexity of Afghanistan’s insurgent landscape.

Mahaz-e-Fedayee Group

Mahaz-e-Fedayee is a militant group active in Kandahar, Helmand, and Uruzgan, known for its involvement in kidnappings, targeted assassinations, and bombings across Afghanistan. It is a splinter faction of Mullah Dadullah’s group, founded by Mullah Najibullah (also known as Omar Khattab). The group has claimed responsibility for several high-profile attacks, including the assassination of Mawlawi Arsala Rahmani, a former Taliban official and a member of the High Peace Council, as well as the bombing outside the Indian Embassy in Kabul. Additionally, two foreign journalists, one Swedish and one British, were killed in Kabul in attacks attributed to Mahaz-e-Fedayee. Mullah Najibullah has stated that the group’s main objective is to derail any peace process between insurgents and the Afghan government, vowing to continue fighting against the Kabul administration and NATO forces until all foreign troops leave Afghanistan. He has also made controversial claims about internal Taliban politics, alleging that Mullah Mansour poisoned Mullah Omar to weaken him before eventually assassinating him and taking leadership. While these claims remain unverified, some reports suggest that such narratives may have been influenced or fabricated by Pakistan’s ISI to manipulate Taliban factions and obstruct peace negotiations.

Brigade 055

Brigade 055 is an elite militant unit within Al-Qaeda, composed primarily of Arab fighters, with an estimated 1,000 to 3,000 members at its peak. Many of these fighters were recruited from prisons during the Soviet-Afghan war and later integrated into the global jihadist movement. When Osama bin Laden relocated to Afghanistan, a significant portion of this unit formally aligned with Al-Qaeda, becoming some of its most dedicated combatants. Historically, Brigade 055 was stationed in Rishkhor military base near Kabul and Qala-e-Jangi in Balkh, playing a crucial role in Al-Qaeda’s operations in Afghanistan. Following bin Laden’s death in 2011, remnants of the unit, estimated at around 500 fighters, continued their armed resistance against the Afghan government and U.S. forces, maintaining their original battlefield tactics. Notably, some members of Saddam Hussein’s former Republican Guard also joined Brigade 055, reinforcing its battle-hardened composition. Despite significant losses over the years, the group remained a persistent force, reflecting the enduring presence of foreign jihadist fighters in Afghanistan’s conflict landscape.

Caucasus Emirate

The Caucasus Emirate, an Islamist militant movement originally founded by Doku Umarov, emerged from the Chechen insurgency after suffering major setbacks against Russian forces. Following its defeat in Chechnya, many of its fighters joined other jihadist movements across the Muslim world, with a faction eventually aligning itself with ISIS and establishing a presence in northern Afghanistan. Previously, around 300 Chechen fighters, some accompanied by their families, were reported to be active in Afghanistan, though their numbers have significantly declined. The group’s leader, Abu Muhammad, was killed, further weakening its influence. Meanwhile, reports indicate that approximately 2,000 foreign fighters from various Central Asian groups, including Chechens, Uzbekistan’s Islamic Movement, and Kazakh militants, have relocated across the Amu Darya river, with some settling in Badakhshan and Takhar provinces.

Among the 24 foreign terrorist groups reportedly active in Afghanistan, at least three are openly hostile toward Pakistan. One such faction, which previously aligned with the Afghan government, was responsible for the attack on a Pakistani military school in Peshawar. Following the incident, the Afghan government handed over a list of the attackers to Pakistan, leading to a Pakistani military offensive that inflicted heavy casualties on the group and forced its remnants into Afghanistan.

According to United Nations estimates, 7,500 to 7,600 foreign fighters continue to engage in combat within Afghanistan. While the Pakistan-Afghanistan border remains a critical battleground, reports suggest that Pakistan plays a key role in directing insurgent activities, while financial backing from Saudi Arabia and Gulf states sustains many of these groups. The complex nature of these transnational networks underscores Afghanistan’s continued role as a theater for global jihadist movements and geopolitical maneuvering.

Unarmed but ideological groups

Hizb ut-Tahrir (HuT)

Hizb ut-Tahrir (HuT) is a global Islamist movement that advocates for the establishment of a Caliphate through political means rather than armed struggle. Unlike the Taliban, Al-Qaeda, or ISIS-K, HuT does not engage in militant activities but instead focuses on ideological mobilization, propaganda, and political activism. In Afghanistan, HuT has operated clandestinely, particularly in urban centers and university campuses, where it has sought to recruit educated youth and professionals. The group has been critical of both democracy and Western-backed governance, advocating for an Islamic system based on its interpretation of Sharia law. Afghan authorities have at times cracked down on HuT’s activities, viewing it as a destabilizing force that could radicalize communities and create ideological pathways to extremism. While HuT does not engage in armed insurgency, its presence in Afghanistan reflects broader ideological currents within the country’s Islamist movements. Its influence remains limited compared to the Taliban and other militant groups, but its non-violent approach to political Islam makes it an alternative ideological force in Afghanistan’s shifting landscape.

Key takeaway

The presence of armed in Taliban-controlled Afghanistan is a continuation of a long-standing reality—one that has shaped the country’s security landscape for decades. While multiple reports suggest that over 20 foreign terrorist groups operate in Afghanistan, the confirmed number stands at 14, with groups such as Al-Qaeda, ISIS-K, TTP, the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU), and Jamaat Ansarullah maintaining an active presence. This sustained militant activity underscores a critical security dilemma: Afghanistan has become a strategic hub for transnational terrorist groups, operating with varying degrees of Taliban oversight.

The Taliban’s relationship with these groups remains ambiguous, despite their formal commitment in the 2020 U.S.-Taliban agreement to prevent Afghan soil from being used as a launching pad for international terrorism. The assassination of Al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri in Kabul in 2022, in a residence linked to Sirajuddin Haqqani, is a clear indication of Al-Qaeda’s continued safe haven under Taliban rule. Reports from the United Nations and intelligence agencies suggest that groups such as IMU, ETIM, and Jamaat Ansarullah have retained operational camps in Afghanistan, further raising concerns about the country’s role in regional and global security threats.

One of the defining characteristics of militant activity in Afghanistan is the fluidity of affiliations and operational networks. Fighters routinely shift between groups based on strategic interests, leadership changes, and battlefield dynamics. The Haqqani Network’s historical ties to Al-Qaeda, coupled with its current integration into the Taliban government, have further complicated efforts to distinguish between groups that operate independently and those that function under Taliban patronage. Similarly, groups such as Lashkar-e-Taiba and Jaish-e-Mohammed, historically focused on Kashmir, have extended their activities into Afghanistan, utilizing its ungoverned spaces to train, reorganize, and plan operations.

Beyond ideology, the Taliban’s rule has also provided access to critical revenue streams, including drug trafficking, resource exploitation, and financial networks that sustain these groups. This has created an environment where militant groups are not only surviving but actively expanding. Reports indicate that several factions are rebranding under new identities, a tactic aimed at reducing international scrutiny while continuing their operations under different names. The Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) and the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM) have reportedly undergone internal restructuring, with new offshoots emerging to continue their objectives with minimal disruption.

Perhaps the most alarming development is the moral and strategic boost that the Taliban’s victory has given to jihadist movements worldwide. The Taliban’s successful resurgence after two decades of warfare has reinforced the belief among other militant groups that perseverance leads to eventual victory. For many jihadist organizations, Afghanistan is now a model of resistance—a place where they can train, regroup, and sustain their ideological struggle without immediate external pressure.

While the Taliban have engaged in conflict with ISIS-K, primarily due to ideological and operational differences, their relationship with other jihadist factions remains largely permissive. The reemergence of terrorist sanctuaries under Taliban rule suggests that Afghanistan may once again serve as a launchpad for transnational militancy, a scenario that presents serious security risks for the region and beyond.