Ghazi Amir Amanullah Khan’s rule was a monarchy, yet he laid the groundwork for democracy in Afghanistan in line with the era’s demands. His efforts later inspired broader freedoms, not just in Afghanistan but across the region. When he ascended the throne in 1919 (1298 Solar Hijri), the world was undergoing major political shifts. The Ottoman Empire had collapsed, authoritarian regimes dominated, and Iran was the only independent country with a constitutional monarchy. If we compare this period with Afghanistan’s neighboring countries, by 1920, Central Asia had fallen under the control of the Russian Bolsheviks, while South Asia—comprising present-day India and Pakistan—remained a British colony. Iran, despite its constitutional monarchy during the Qajar period and under Reza Shah, functioned as an authoritarian state. The key difference between Iran and Amanullah Khan’s Afghanistan was that Amanullah actively pursued constitutionalism, whereas Iran’s monarchy had it imposed upon them.

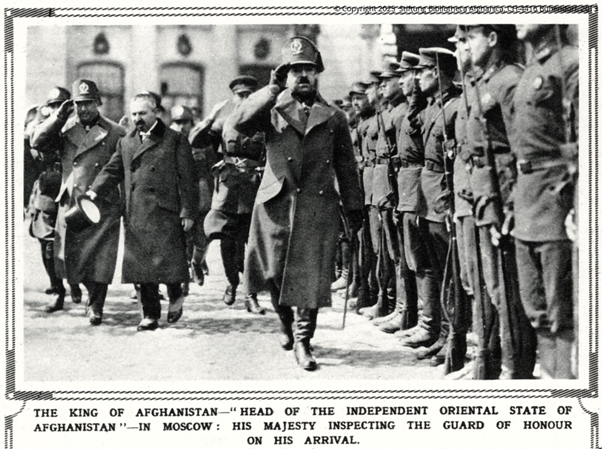

The King of Afghanistan, His Majesty, Ghazi Amir Amanullah Khan, inspecting the guard of honor, Moscow.

During Amanullah Khan’s reign, significant steps were taken to strengthen democracy in Afghanistan. The country’s engagement with democratic values did not begin in 2001 but dates back to the early 20th century. Afghanistan’s first legal code was, in some aspects, even more democratic than Britain’s system at the time. Amanullah Khan drew inspiration from his father, Amir Habibullah Khan, who had attempted to introduce democratic principles during his brief rule. These efforts gained momentum with the rise of the Mashrootiat (Constitutionalist) Movement, which played a key role in shaping Afghanistan’s democratic trajectory. The country’s experience with democracy spans over a century, beginning under Amir Habibullah Khan and the influence of the Mashrootiat Movement. This movement, guided by scholars like Sayyid Jamaluddin Afghan and Mahmoud Tarzi, pushed for the rule of law, separation of powers, and limitations on monarchical authority. When Amanullah Khan came to power and secured Afghanistan’s independence, these principles were formally codified in the country’s first constitution, Nizamnama Asasi Dawlat-e-Ali Afghanistan (The Fundamental Law of the High State of Afghanistan). Additionally, nearly a hundred other legislative documents, known as Nizamnamas, were enacted—marking a critical step toward institutionalizing democracy.

Afghanistan’s first constitution, Nizamnama Asasi Dawlat-e-Ali Afghanistan, was ratified early in Amir Amanullah Khan’s rule on March 1, 1923 (10th of Hoot, 1301). It enshrined key democratic principles, including Article 9, which safeguarded Afghan independence from external aggression, Article 17, which granted equal rights to all Afghans based on Islamic law, and Article 20, which protected homes from unlawful intrusion. Additionally, Article 24 prohibited torture, and Article 39 mandated the creation of governmental councils (shuras) at various levels, including the capital, provincial governors (Naib-ul-Hukuma), and other administrative divisions. Despite these democratic strides, Amanullah Khan’s reforms collapsed following the rise of Habibullah Kalakani and the king’s exile, dismantling Afghanistan’s first major attempt at democratic governance. His removal thwarted all efforts toward institutionalizing democracy, and the country entered decades of autocratic rule.

Democracy flourishes when embedded within society, but much like economic, educational, and political development, it failed to take sustainable root in Afghanistan. Reform efforts faced resistance from both internal and external adversaries, and Amanullah Khan’s ambitious changes outpaced the country’s readiness. Without a strong military to maintain stability, his rapid reforms ultimately led to his downfall. After multiple failed attempts at democratization, a new wave of reforms emerged during one of Afghanistan’s more promising periods— the “Decade of Democracy” (1964–1973), under King Mohammad Zahir Shah. This era saw the abolition of absolute monarchy, a new constitution, and the legalization of political parties, along with guarantees of free speech and an independent press. However, like past democratic efforts, this period, too, faced structural weaknesses that would later contribute to its unraveling.

King Zahir Shah with Queen Elizabeth II in London

Although the Decade of Democracy officially began in 1964 (1343 Solar Hijri), Afghanistan had already taken democratic steps between 1949 and 1954 (1328–1333 Solar Hijri) under the premiership of Shah Mahmud Khan. This earlier period saw the emergence of political parties, an active press, and electoral processes, laying the foundation for later democratic advancements. The 1964 Constitution, enacted on September 30, 1964 (9 Mizan 1343 Solar Hijri), introduced key democratic principles. Article 31 protected freedom of thought and expression, allowing Afghans to express opinions through speech, writing, and photography within legal boundaries. It also granted them the right to publish freely without prior government approval. Article 32 provided the right to peaceful assembly and the formation of political parties, further strengthening Afghanistan’s democratic framework. The 1964 Constitution governed Afghanistan until 1973 and is widely regarded as one of the country’s most democratic eras. At a time when much of Asia and the Islamic world remained under absolute monarchies except for Japan Afghanistan stood out as a regional model of democracy. This period saw the establishment of democratic institutions, the enactment of independent press laws, the introduction of electoral processes, and parliamentary accountability. Although a formal law on political parties was never enacted, parties began to operate informally, making this Afghanistan’s second major democratic phase.

Many Afghans still recall the Decade of Democracy as a rare period of political openness, yet its legacy remains contested. In 1973 (1352 Solar Hijri), Sardar Mohammad Daoud Khan, a member of the royal family, staged a coup, abolishing the monarchy and declaring a republic. This raises an important question: Did the Decade of Democracy contribute to the coup against Mohammad Zahir Shah? While it introduced democratic institutions, it also exposed deep structural weaknesses. Daoud Khan was dissatisfied with the 1964 Constitution, and the system itself faced serious challenges. Corruption was widespread, parliament had become a breeding ground for political brokerage, and both leftist and rightist factions had infiltrated the armed forces, backed by competing foreign powers. Rumors of rebellion and coups circulated, and in a bloodless coup (White Coup), Daoud Khan overthrew the monarchy. During his five-year rule, Daoud Khan sought to consolidate a republican system, yet he failed to establish democratic foundations. No parliament was formed, no constitution was ratified, and no elections were held to institutionalize governance. His vision of a strong republic collapsed with the April 27, 1978 (7 Saur 1357) coup, orchestrated by the Khalq and Parcham factions of the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA). The PDPA’s promises of transformation were soon overshadowed by repression and internal strife. Their war with the Mujahideen mirrored the Mujahideen’s later descent into factionalism, while the Taliban’s version of an Islamic state also remained incomplete. None of these groups upheld democratic principles. The Khalq and Parcham factions rejected democracy as a Western construct and imposed their own ideology as the foundation of governance. Their rule was marked by mass imprisonments, executions, and brutal suppression of dissent, culminating in the infamous Pul-e-Charkhi Polygons, where countless political dissidents were sent to their deaths.

Afghanistan’s ‘Decade of Democracy’ under King Mohammad Zahir Shah

Islamic factions, including the Taliban, rejected democracy as incompatible with Islamic principles and violently suppressed pro-democracy movements. However, the 21st century ushered in a new chapter in Afghanistan’s history with the fall of the Taliban regime following the 9/11 attacks. The U.S.-led international coalition intervened militarily, aiming to dismantle Al-Qaeda and overthrow the Taliban. After decades of civil war and authoritarian rule, Afghans embraced the opportunity to rebuild their country under a democratic system. The interim and transitional governments, followed by elected administrations, worked to lay the foundations of a new political structure. Despite challenges, one of the most significant milestones was the adoption of a new constitution, which in principle, enshrined democratic values, protected individual freedoms, and promoted human rights. For the first time in Afghanistan’s history, an Independent Human Rights Commission was established to oversee the protection of civil liberties. The Afghan Constitution’s Article 4 declared that national sovereignty belonged to the people, while Article 6 outlined the government’s duty to protect human dignity, uphold democracy, ensure national unity, promote equality, and pursue social justice to create a prosperous society. These constitutional guarantees marked a shift away from authoritarianism, giving Afghans renewed hope. The fall of the Taliban in 2001 brought tangible changes—schools reopened for boys and girls, gender-based restrictions were lifted, independent media flourished, and censorship on speech and expression was abolished. However, despite these advances, neither security nor democracy fully took root. The Afghan government remained dependent on foreign aid, and governance structures lacked legitimacy. It is crucial to recognize that the U.S. did not overthrow the Taliban primarily to establish democracy. Instead, Washington’s focus was on counterterrorism and state-building as a means to prevent Afghanistan from becoming a terrorist safe haven again. The establishment of democratic institutions was secondary, and while some individuals benefited from these reforms, the majority of the population saw little tangible improvement in their daily lives. Democracy in Afghanistan was externally driven rather than organically developed, which ultimately contributed to its fragility.

Afghanistan’s Constitution after 2001.

Over the past two decades, in addition to the Constitution, several efforts were made to strengthen democracy in Afghanistan. One of the most significant developments was the rapid expansion of civil society. Numerous organizations emerged, advocating for human rights, women’s empowerment, press freedom, and democratic governance. However, civil society in Afghanistan remained fragile due to two fundamental challenges. The first issue was that civil society became deeply intertwined with political agendas and heavily reliant on foreign funding. Many organizations operated as extensions of international donor programs, rather than as independent, community-driven initiatives. With the withdrawal of international actors, funding dried up, and most civil society activities came to a standstill. The lack of grassroots ownership meant that these institutions had no long-term sustainability, leaving Afghan society vulnerable when foreign support ceased. The second, and arguably larger, mistake was the neglect of Afghanistan’s traditional civil society structures. Unlike the modern NGOs concentrated in urban centers, Afghanistan’s historical civil society existed in rural villages, tribal councils/elders, mosques, community councils (jirgas), local assemblies (shuras), and traditional conflict-resolution forums (marakas). These institutions had long served as the foundation of local governance, mediating disputes and maintaining social cohesion. Unfortunately, the international community and Afghan elites largely ignored these structures, creating a divide between state-imposed democracy and indigenous governance traditions. For two decades, Afghanistan experimented with democracy within a framework of institutional governance, elections, and constitutional rule. However, the fundamental gap remained: Why did democracy fail to take root, and why was it not fully utilized? The answer lies in the disconnect between Western-imposed democratic models and the realities of Afghan society. The Afghan political system was never fully owned by the people, as it operated more as a donor-driven project rather than a governance system that evolved naturally from Afghan traditions and political culture. This disconnect ultimately contributed to the collapse of democratic institutions when foreign support was withdrawn.

The Afghan government was largely composed of political and administrative forces that were not inherently democratic and struggled to adapt to democratic norms. Many Afghans perceived democracy as a foreign or non-religious concept, which created a sense of alienation from the system. This disconnect resulted in missed opportunities, as key institutions such as elections and the separation of powers failed to function effectively. While democracy, in principle, is a system meant for all, Afghanistan was unable to develop structures that aligned with its governance traditions. Instead, authoritarian networks and hegemonic power structures retained control, marginalizing progressive forces and keeping the country in a cycle of uncertainty and stagnation. The 2004 Constitution enshrined principles of equality, human rights, and freedom of expression. Article 22 guaranteed equal rights for men and women, Article 24 mandated the protection of individual freedoms and dignity, and Article 34 safeguarded freedom of speech. However, despite these constitutional assurances, democracy in Afghanistan remained fragile, as entrenched elites resisted reforms that threatened their power. Nevertheless, Afghan women made remarkable strides, playing an active role in politics, education, and civil society. This stands as one of the most notable achievements of the democratic period. Another major success was the growth of independent media, which provided transparency, free speech, and access to unbiased information. Afghanistan’s media landscape flourished during this time, offering a platform for political debate, investigative journalism, and public discourse. However, these gains remained highly vulnerable, as they were dependent on foreign support and fragile democratic institutions, making them susceptible to collapse when the political environment shifted.

Elections are the foundation of any democratic system, and Article 33 of the Afghan Constitution affirmed that all Afghan citizens had the right to vote and run for office. The constitution provided for seven types of elections, including presidential, parliamentary, district council, and municipal elections. However, due to persistent insecurity, violence, and administrative weaknesses, only three types of elections were ever held, and even those were plagued by serious challenges. A 2021 report by the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) revealed that the international community spent approximately $1.2 billion on Afghanistan’s electoral system since 2001, with the United States contributing at least $620 million. Despite this massive investment, the results were weak, as Afghanistan’s electoral institutions failed to establish transparent, reliable voting processes. SIGAR highlighted severe mismanagement, electoral fraud, and security concerns, all of which undermined public trust in elections. Article 35 of the Afghan Constitution granted Afghans the right to form political parties, provided they adhered to legal frameworks. By the time of the republic’s collapse, 72 political parties had been officially registered under the Ministry of Justice. However, despite constitutional restrictions against parties forming along ethnic, regional, linguistic, or religious lines, Afghan politics remained deeply fragmented along these very divisions. Political parties failed to develop strong ideological foundations, and instead, many operated as personal patronage networks, further weakening democratic governance. Ultimately, while elections were held, they did not strengthen democracy in a meaningful way. Widespread fraud, voter intimidation, and the influence of warlords and powerbrokers rendered the electoral process ineffective in fostering genuine political representation. The failure to establish a credible, independent electoral system played a crucial role in Afghanistan’s democratic collapse, as public confidence in democratic institutions eroded over time.

Afghan Parliament, 2019.

Afghanistan’s political parties, in theory, had no structural barriers to their formation, and the past two decades saw notable progress in their legal recognition. However, in practice, the absence of strong, organized political parties in parliament severely undermined governance. Instead of functioning as cohesive blocs, most members of parliament (MPs) acted as independent political actors, often shifting allegiances based on personal interests rather than party principles. This fluid and unpredictable dynamic weakened parliamentary integrity and contributed to chronic instability. MPs would support the government one day and oppose it the next, often in exchange for political or financial incentives. The lack of a party-based parliamentary system was a fundamental weakness in Afghanistan’s democratic experiment. Without established political parties, parliamentary debates frequently descended into personal disputes, sometimes escalating into verbal altercations and even physical confrontations. On multiple occasions, security forces forcibly removed MPs from the legislative chamber, highlighting the dysfunction within Afghanistan’s political system. One of the key reasons Afghanistan failed to develop a party-based system was the absence of a moderate, unifying political ideology. Instead of forming ideological coalitions, political parties remained fragmented, often built around ethnic, regional, or factional loyalties rather than policy-driven platforms. This lack of ideological coherence made it impossible for parties to consolidate and establish a stable political system. Despite these political shortcomings, Afghanistan’s democratic experience did produce some progress. Over two decades, democracy contributed to relative economic growth, increased international engagement, the expansion of women’s rights, and advancements in various sectors. However, Afghans developed their own interpretations of democracy, shaped by their historical, social, and political realities. Many viewed democracy not as a governance system deeply embedded in society but as an externally imposed framework, which further complicated its acceptance and long-term sustainability.

Democracy embodies freedom—the right to express oneself, to raise one’s voice, and to claim one’s rights. Despite Afghanistan’s many challenges, the past two decades witnessed notable progress for Afghan women, who gained access to government positions, education, and social leadership. After the U.S. intervention, international efforts—combined with the determination of Afghan youth and the resilience of Afghan women—pushed forward women’s rights and democratic participation. Although this progress was incomplete, it marked a significant shift in Afghan society, demonstrating that even in a fragile system, individuals could carve out spaces for advocacy and reform. Democracy, however, is interpreted differently by different societies. The post-World War II and Cold War periods saw democracy flourish in many war-torn nations, where leaders became accountable to the people who elected them. Yet, this did not happen in Afghanistan. Instead, the influx of Western aid and foreign influence reshaped governance, making Afghan officials more accountable to international donors than to their own citizens. Elected governments thrive when they are answerable to their own electorate, but in Afghanistan, billions of dollars in aid conditioned Afghan leaders to prioritize the demands of foreign stakeholders over those of the Afghan people. Instead of building self-sustaining democratic institutions, political elites depended on foreign support, and as a result, governance became a donor-driven project rather than a homegrown system of accountability. In reality, the Western military intervention itself became an obstacle to consolidating democracy. While it aimed to build a democratic Afghan state, it also undermined organic political evolution, as Afghan leaders focused on maintaining foreign backing rather than engaging with their own constituents. This disconnect between the government and the people ultimately contributed to Afghanistan’s democratic collapse, as state institutions remained fragile and lacked public trust when international forces withdrew.

Women stand in line to vote at a polling station in Herat. [Hoshang Hashimi/AFP]

The 14th century of the Solar Hijri calendar, which began with Afghanistan’s independence under Amir Amanullah Khan, has ended, leaving behind a history of conflict, brief stability, and lost opportunities. Over the past fifty years, the country has oscillated between war and fleeting moments of peace. For most Afghans, memories of stability are distant. With over 60% of the population born into conflict, few recall a time before war. This generational reality has shaped Afghanistan’s national identity, where instability has become the norm rather than the exception. As Afghanistan moves forward, its trajectory remains uncertain. The lessons of the past century—from Amanullah Khan’s reforms to the fall of democracy in 2021—underscore the recurring structural failures that have prevented lasting stability.

Over the past 100 years, Afghanistan has experienced seven different political systems and ten forms of governance, shifting between monarchy, republics, socialist rule, and Islamic states. Among these, the Constitutional Monarchy under Zahir Shah lasted 40 years, making it the longest-standing political system in modern Afghan history. Amanullah Khan took power in 1919 (1298 Solar Hijri) after the assassination of his father, Habibullah Khan. His modernization efforts transitioned Afghanistan from an absolute monarchy to a constitutional monarchy, a system that continued under Habibullah Kalakani, Nadir Shah, and Zahir Shah. However, in 1973 (1352 Solar Hijri), Daoud Khan overthrew Zahir Shah in a coup, establishing a republic. For over a century, Afghanistan’s governments have failed to establish a functional, law-based system that reflects the will of the people. Governance has never been built on true public consensus, leading to cycles of instability and power struggles. After five years of Daoud Khan’s rule, the Khalq Party’s Revolutionary Council seized power in 1978, renaming the country the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan. Over the next decade, a Soviet-backed socialist republic was led by Nur Mohammad Taraki, Hafizullah Amin, Babrak Karmal, and Dr. Najibullah. In 1992 (1372 Solar Hijri), the Mujahideen established an Islamic State, which lasted until 1996 (1375 Solar Hijri) when the Taliban seized Kabul, executed Dr. Najibullah, and declared an Islamic Emirate. Following the 9/11 attacks in 2001, the U.S. military intervention led to the fall of the Taliban. The Bonn Conference established a new Islamic Republic, first under Hamid Karzai, later succeeded by Ashraf Ghani. This republic collapsed in August 2021, with the Taliban’s return and the re-establishment of the Islamic Emirate, which remains in power today. Despite these repeated transitions, Afghanistan’s political future remains uncertain, shaped by war, ideological shifts, and the struggle for lasting governance.