By definition, ifrat or extremism means going beyond reasonable limits or engaging in excess. In practice, extremism means straying from the path of moderation and reason. It’s about not only clinging stubbornly to one’s own beliefs while rejecting the views and ways of others as wrong or invalid, but also superimposing your own beliefs on others, no matter what.

True rationality calls for a genuine commitment to truth. It means accepting ideas only when they are backed by logic and evidence. Extremism, on the other hand, tends to be self-centered. It places one’s own beliefs and ideas above all else as if they alone represent the truth. It dismisses other perspectives outright and refuses to allow space for reflection or reconsideration. In such a mindset, reason and rational thought are pushed aside, replaced by illusions fueled by selfish desires and destructive intentions.

Extremism can take many forms. It can be based on ethnicity, race, political ideology, group affiliation, or religion. But no matter its form, extremism is usually rooted in rigid prejudice, a break from moderation and rationality, and a departure from genuine religious teachings.

History of extremism in Afghanistan

More than twenty extremist groups, operating under the guise of religion, were/are active across various parts of Afghanistan. This situation raises several urgent and complex questions. How did these groups emerge? What factors enable their continued presence? Are they the product of Afghanistan’s internal challenges, or have foreign powers played a decisive role in fostering and supporting them? If external actors are involved in their creation and sustenance, why was Afghanistan chosen as their base? Was it the country’s internal vulnerabilities that made it fertile ground for extremist ideologies, or was Afghanistan’s strategic geopolitical position the main attraction? A large number of questions bombard our minds when speaking of extremism and radicalism in Afghanistan. However, at the heart of these questions lies a fundamental concern: can Afghan society, particularly after the Taliban’s return to power in 2021, when extremism reached its peak, realistically advance toward economic development, social stability, and a promising future?

Addressing these issues requires comprehensive research, informed analysis, and the collective efforts of scholars, policymakers, and civil society actors. Only through such coordinated action can Afghanistan hope to break free from the cycle of extremism and radicalism that continues to hinder its progress.

The use of religion as a tool for driving extremist movements in Afghanistan goes back about a century. After Afghanistan’s victory in the Third Anglo-Afghan War, when the British were forced to recognize the country’s full independence, Afghanistan’s regional importance grew more than ever. Along with independence came the creation of the first modern, national government in Afghan history based on a constitution approved by a Loya Jirga (grand consultative assembly). Around the same time, Afghanistan’s entry into international relations opened new doors for cooperation and paved the way for future development.

But it was also at this critical point in history that colonial powers launched a new wave of conspiracies against Afghanistan. On one side, they worked to block King Amanullah Khan’s reforms, and on the other, they aimed to stop Afghanistan’s freedom movement from inspiring people in neighboring areas still under colonial control. To achieve this, they ramped up sabotage and propaganda efforts across the country. In 1923, a cleric named Mullah Abdullah, better known as Mullah Lang (the Lame Mullah), opposed the government’s new penal code. Using “Sharia advocacy” as his slogan, he led an uprising in Paktia. He was often seen in public gatherings holding a Quran in one hand and the new Constitution in the other, asking people: “Which one do you choose?” After this rebellion, British intelligence, using its connections with certain religious leaders and recruiting Qadiani, Salafi, and Deobandi clerics, helped organize extremist activities against the Afghan government. Jawaharlal Nehru described this manipulation in Glimpses of World History, pointing out how large sums of money were spent on propaganda against Amanullah Khan. According to Nehru, nobody knew where the money was coming from, but it was widely believed in both the Middle East and Europe that British secret services were behind it.

As a result, even though King Amanullah was celebrated abroad—in Muslim countries as a great Mujahid and in Europe as a hero who defeated British colonialism—he was targeted by poisonous British propaganda back home. In the end, this campaign succeeded in bringing down his government. The constitutional monarchy that had been built on the sacrifices of countless Afghan patriots was ultimately overthrown.

The fall of King Amanullah Khan didn’t just accomplish the colonial powers’ immediate goals—it left behind long-lasting damage. For years afterward, Afghanistan was stuck in a cycle of repression and setbacks. It wasn’t until the Seventh Session of the National Assembly that Prime Minister Shah Mahmud Khan agreed to introduce a few basic freedoms. But even those didn’t last. Not long after, those who spoke out for change—some of the most respected activists of the time—were arrested and silenced. The years between 1929 and 1965 became a period of suffocation for moderate and reformist ideas. The momentum that had once existed during the constitutional movement was broken, and as a result, when new intellectual and political movements began to reappear during the so-called “Decade of Constitutionalism or Democracy,” they lacked the depth, maturity, and experience they needed to make a lasting impact.

By the 1960s, after more than three decades of absolute rule, the government itself initiated a shift toward a constitutional monarchy. But this wasn’t entirely driven by democratic ideals. The ruling elite had two main objectives: first, to adjust to the changing global political climate, and second, to marginalize internal rivals within the royal family. During this period of transition, extremist groups once again found space to resurface. They reappeared across the country, but their activities were especially focused on Kabul. These groups came from two opposing camps—left-wing and right-wing factions. Yet, despite their sharp differences, neither side was really addressing the actual problems and needs of Afghan society at the time.

Extremism under the banner of leftist ideologies

Like many developing countries at the time, Afghanistan’s leftist movements were heavily influenced by the ideological propaganda of the two major socialist centers of power—Moscow and Beijing. Those Afghan activists who followed Beijing’s lead were convinced that China’s revolutionary model could be replicated in Afghanistan. They believed their country’s social and economic conditions made it ripe for such a movement, yet they ignored the reality on the ground—Afghanistan’s unique political and social dynamics. Quoting Mao Zedong, they called for mobilizing the peasantry and surrounding the cities from the countryside. They dismissed peaceful political engagement as a waste of time and saw armed struggle as the only path to power. To them, participating in parliamentary elections was pointless. They argued that parliaments were nothing more than arenas where elites bargained over their own interests, leaving the working class behind.

In terms of foreign policy, they rejected the principle of “peaceful coexistence,” viewing it as nothing but a backroom deal between Soviet “social imperialists” and American imperialists. But these extreme leftist slogans failed to win much support in Afghan society. As a result, their organizations fragmented, and many of their networks collapsed in the wake of unfolding events. Extremism wasn’t limited to the followers of Beijing’s line. Among the supporters of the Soviet-backed faction, there were also individuals who believed in armed uprisings. One prominent figure was Hafizullah Amin. He took advantage of a volatile political moment and seized state power without the consent of the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA) leadership.

When Mir Akbar Khyber, a senior figure in the PDPA’s Parcham faction, was assassinated, his funeral turned into a massive show of force. The regime saw this as a direct threat and ordered the arrest of several party leaders, including Amin. While others were detained quickly, there was a suspicious delay in Amin’s arrest. This delay gave him enough time to secretly pass instructions to loyal military officers. Although Amin wasn’t formally part of the party’s top leadership, he had long been tasked by Noor Mohammad Taraki to recruit and organize officers in the PDPA’s Khalq faction within the armed forces.

Taking advantage of the growing tensions between the party and the government, Amin moved swiftly. He directed his network of officers to act against the government in the name of the party. This allowed him to tighten his grip on the military and, eventually, take control of the state. As more of Amin’s loyalists took up key positions in the armed forces, his authoritarian rule grew stronger, and the country descended into deeper chaos. Accounts from PDPA leaders and other documents from the time make it clear that Amin was actively working to dismantle state institutions and sow divisions within the nation. His reign of terror began with the brutal massacre of President Daoud Khan and his family and expanded to widespread killings across Afghanistan. Religious leaders from moderate Sufi orders, intellectuals, scholars, teachers, workers, and even members of other political groups, including those within the PDPA itself, were targeted and executed. An estimated four thousand PDPA members were killed by Amin’s faction alone—more than half of them from the Parcham faction. Many others were imprisoned without cause.

As Amin’s crimes mounted, many within the party demanded his removal. But he remained protected by powerful unseen forces. It was only after he murdered his mentor, Noor Mohammad Taraki, that his foreign supporters and rivals inside the regime could no longer ignore who he really was. Once his backers withdrew their support, Amin’s protective shield crumbled. Soviet forces moved quickly, eliminating him within hours and clearing the way for the PDPA leadership to retake control.

After Amin was removed, there was broad agreement that the damage he had done to the state had to be repaired immediately. The day after his death, prison doors were opened, and thousands of detainees were released and returned to their lives. Soviet troops, who had already secured key strategic locations in Afghanistan weeks before Amin’s fall, now offered their full backing to the new leadership. While this helped restore the Afghan military to some degree, it also gave Pakistan and its Western allies a convenient excuse to escalate support for the opposition groups they favored—arming them with advanced weaponry. Plenty of documents and reports have been written about Amin’s brutality. After assassinating Taraki, Amin even posted a list of 13,000 executed prisoners on the walls of the Ministry of Interior, hoping to blame the killings entirely on Taraki. But no one was fooled. People knew that Amin was the true architect of those crimes. And beyond the names on that list, thousands more innocent lives were lost because of his actions.

Extremism disguised as Islam

In the late 1960s, networks linked to the Muslim Brotherhood (Ikhwan al-Muslimin) began forming in Afghanistan. Based on their actions and ideology, they soon proved to be part of the far-right extremist current. From the beginning, these groups didn’t bother to introduce any clear vision or program to the public. Instead, they turned straight to undermining security and disrupting society. In many ways, they resembled the religious reactionaries who had surfaced a century earlier—opposing modern life, rejecting civil liberties, and dragging Afghan society backward. One of their first targets was women’s freedom. As the late Hasan Kakar noted, religious extremists would stand outside university campuses and attack women they deemed improper. Women who were not wearing the veil became victims of acid attacks. Two hundred women were hospitalized with severe burns.

But the violence didn’t stop there. These groups also began targeting intellectuals and political gatherings that didn’t align with their rigid views. Despite the fact that Afghanistan had a parliament and space for legal political activity, these groups chose violence and illegal methods instead. Much of their thinking was influenced by clerics working closely with Pakistan’s intelligence agencies, whose agenda often involved using religious slogans to justify interference—whether in Afghanistan, Kashmir, or against the Pashtuns and Baloch within Pakistan itself. By 1972, one of these groups, Jamiat-e Islami, quietly announced its formation. It didn’t take long for splinter groups to emerge, each with its own agenda. After the 1973 coup, Jamiat-e Islami’s original leaders were jailed, while many others fled to Pakistan. It was there, with the involvement of these exiles, that several failed plots against Mohammad Daoud Khan’s republic were hatched.

When their armed rebellions and conspiracies failed, many of these Islamists realized they had little support among Afghans. That drove even more of them to relocate to Pakistan, where they came under the wing of Pakistan’s military intelligence. What followed was increased tension between Afghanistan and Pakistan, a situation that ultimately benefited the Islamists. As relations soured between the two governments, these groups gained more influence and legitimacy in Pakistan’s eyes. Soon after, Pakistan established military training camps for them. Thousands were quickly trained to wage war inside Afghanistan. As the standoff between Kabul and Islamabad intensified, the Cold War superpowers also dug in. Pakistan’s alliance with the West meant it received even more aid for supporting opposition groups, while the Soviet Union stepped up its backing of the Afghan government. Afghanistan, once proud of its non-aligned status, was pulled deeper into regional turmoil.

After Daoud Khan’s republic collapsed, extremist groups gained even more support. They were flooded with weapons, money, and political backing. Their violent campaigns were rebranded as an “Islamic mission” under the banner of jihad. To better control them, their foreign sponsors—especially in the Arab world—preferred to split them into smaller factions. This way, they could be managed more easily. Wealthy Arab sheikhs poured money into these groups, while some areas under their influence became safe havens and training grounds for international extremists.

Mahfoud Bennoune, an Algerian sociologist, warned in 1996 that these fighters posed a global threat. In an interview with the Los Angeles Times, he said:

“The nucleus of these extremists was built in Pakistan for Afghanistan’s war… and now that nightmare has spread to Algeria and beyond. Sixteen thousand Arabs who trained for Afghanistan have become a killing machine.”

By 1992, reports estimated that nearly 48,000 Arabs had fought in Afghanistan or received military training there. When they returned home, they were known as “Afghans,” and in many places, they became a serious problem by spreading extremist ideologies. The seven factions in Pakistan and eight in Iran (later united as Hezb-e Wahdat) had one thing in common: their extremist worldview. This was made clear by their refusal to tolerate one another. When they returned to Afghanistan, instead of working together, they engaged in bloody infighting. Their battles caused immense suffering for ordinary Afghans caught in the middle.

This shared extremism also tied them closely to the Taliban. Just like the Taliban, they followed the orders of their foreign backers and pushed the same extremist ideologies. As reported by international media, many of these fighters were not only active in Afghanistan but also sent to stir unrest in Central Asian republics. Leaders from Hezb-e Wahdat even admitted with pride that thousands of Afghans had been recruited by Iran as part of the Fatemiyoun Division to fight in Syria and Iraq. Once Pakistan succeeded in breaking Afghanistan’s state institutions and military through these proxy groups and Iran-backed factions, they introduced the Taliban as the new power in Kabul. The Taliban picked up where these groups left off, taking extremism to another level and ignoring the core principles of moderate Islam. Under Taliban rule, the settlement of Arab and foreign extremists in Afghanistan intensified. Saudi Arabia, in particular, wanted its dissidents to stay away from home—and Afghanistan became the dumping ground. The Taliban welcomed them and, in return, received generous financial support from the Saudis and other sponsors of extremism. The Taliban handed over abandoned Afghan military bases to al-Qaeda and offered top accommodations to their families. While the Taliban benefitted from these deals in the short term, their fortunes took a sharp and unexpected turn. The 9/11 attacks, carried out by al-Qaeda operatives nurtured in Afghanistan, changed everything.

With al-Qaeda headquartered in Afghanistan, the United States and NATO launched a military campaign aimed at wiping out both al-Qaeda and the Taliban. While they were ousted from power, Afghanistan didn’t move toward the peace and progress many had hoped for. Instead, power fell into the hands of war profiteers, warlords, and bureaucrats with little connection to the Afghan people. This created fertile ground for the Taliban and other extremist groups to regroup and relaunch their insurgency. Helped by foreign sponsors and fueled by public frustration, these groups regained strength—militarily and politically. Their resurgence reached the point where they became negotiating partners with the United States. Today, they’re pushing to reimpose their extremist ideologies on both Afghan society and the international community.

Sadly, once again, the Afghan people have been left out of decisions about their country’s future. The same faces that once brought misery to Afghanistan are still calling the shots—driven by personal gain rather than the national interest. For them, the Taliban’s ideology and foreign interference are just part of the game.

The Taliban’s return and the escalation of extremism

The return of the Taliban to power in 2021 has had far-reaching and destructive consequences, both within Afghanistan and across the broader region. Their resurgence has effectively transformed Afghanistan into a fertile ground for the proliferation and entrenchment of extremist ideologies. While the immediate impacts are clear, the long-term repercussions of this crisis will likely continue to unfold for years to come. Perhaps the most alarming outcome of the Taliban’s second ascent has been the sharp acceleration in extremist mobilization—both ideologically and operationally.

Since regaining control, the Taliban have not only reinstated their previous patterns of governance but have also strengthened partnerships with a range of extremist groups. These actors are now active throughout the country, having established recruitment and propaganda hubs that offer both ideological indoctrination and paramilitary training. This infrastructure serves a dual purpose: reinforcing Taliban rule and preparing for potential future threats to their regime. While extremism in Afghanistan has deep historical roots—stretching back more than four decades—the Taliban’s return has solidified and institutionalized it in unprecedented ways. Afghanistan today stands as a central node in the global network of radical ideologies. Public and private spaces alike, from religious institutions to ethnic and communal structures, have become deeply entangled with extremist narratives. As a result, extremism has permeated nearly every facet of Afghan life.

Two predominant models of extremism continue to dominate Afghanistan’s landscape: religious fundamentalism rooted in hardline interpretations of Islam, and ethnic chauvinism driven by exclusionary identity politics. Together, they fuel an environment where moderate voices are increasingly marginalized. Over the years, religion has been relentlessly instrumentalized by power-hungry actors as a mechanism of control. Groups like the Taliban have perfected the use of religious extremism as a governing tool, recognizing that their regime’s survival hinges on embedding radical ideology across all levels of Afghan society. Recent reports illustrate the deepening nature of this crisis. The Long War Journal, for example, published a treatise by Saif al-Adl, the current leader of al-Qaeda, calling on the group’s affiliates to relocate to Afghanistan, learn from the Taliban’s model, and continue the so-called “global jihad.” This is not an isolated development. The UN Security Council has already confirmed the presence of al-Qaeda bases across multiple Afghan provinces. At the same time, reports indicate active collaboration between the Taliban and transnational extremist factions such as Tajikistan’s Ansarullah and Uzbekistan’s Islamic Movement. These groups are believed to be receiving training on Afghan soil, preparing for future insurgencies in their respective regions.

Concurrently, Salafi groups are aggressively expanding their reach within Afghanistan. These groups, with tacit support from elements within the Taliban, have taken control of religious schools and educational institutions. Their role in fueling sectarian division and religious intolerance is well-documented. Through educational control and targeted propaganda, they continue to advocate for violence as a legitimate tool to expand their ideological influence. Groups like the Taliban, whose regime remains fragile and under threat, increasingly view the spread of extremist ideology as a strategic necessity rather than a liability. This has critical implications for Afghanistan’s social fabric. As long as extremist factions remain under Taliban protection, the prospects for pluralism, diversity, and tolerance in Afghan society will continue to diminish—if not disappear entirely.

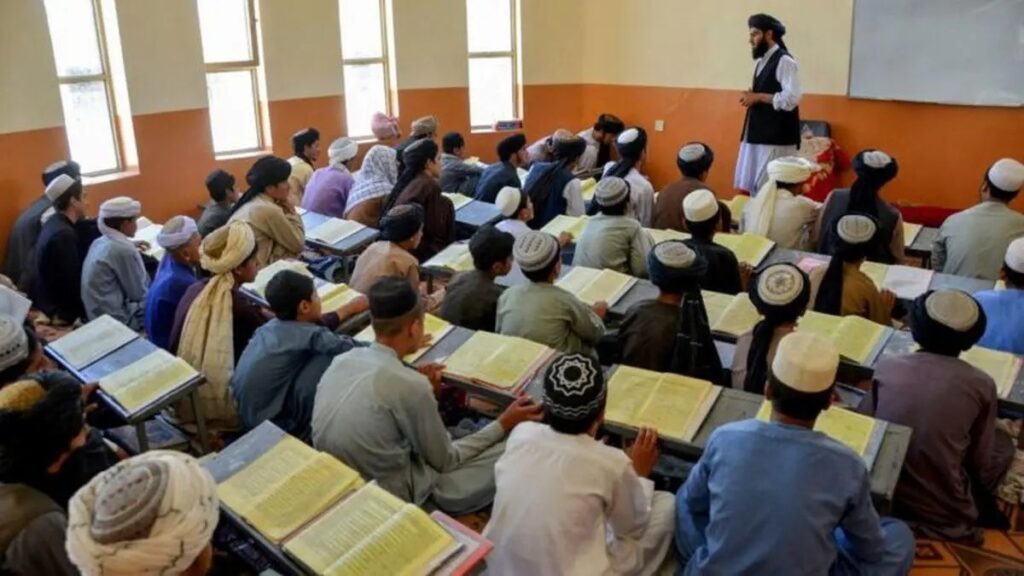

A key pillar of the Taliban’s ideological project is their comprehensive control over Afghanistan’s educational infrastructure. Estimates indicate there are now more than 21,000 religious madrasas operating in Afghanistan, with their numbers having surged dramatically since the Taliban’s return. Millions of children—boys and girls alike—are exposed to extremist indoctrination every year. If this trajectory continues unchecked, Afghanistan is at risk of becoming the epicenter of global extremism, with dire consequences for regional and international security. The Taliban’s revision of the national education curriculum is not merely a policy choice but a deliberate strategy aimed at institutionalizing radicalism. This process of Talibanization within education is expected to have a crippling effect on Afghanistan’s long-term development. By replacing critical thought with ideological rigidity, the Taliban are systematically dismantling avenues for intellectual growth and enlightenment. They fully understand that an educated and critically engaged generation would pose an existential threat to their regime. For this reason, they have invested heavily in the production and reinforcement of extremist ideology as a means of power consolidation.

In this context, Afghanistan’s universities have also been co-opted. Once envisioned as centers of learning and inquiry, they have now been transformed into bastions of religious indoctrination. Curricula no longer promote scholarship or foster analytical thinking. Instead, they propagate outdated narratives, presenting the world in stark binaries—dividing it into a “world of Islam” versus a “world of infidels.” Afghan children are being conditioned from an early age to reject modernity, technological advancement, and global engagement. They are taught to view the world through a lens of suspicion and hostility. Such educational policies do not merely reflect ideological ambition; they actively contribute to the marginalization and isolation of Afghan society. Stories abound of young Afghans who, shaped by years of extremist education, reject the values, practices, and aspirations of modern life. These patterns are not incidental but are a direct consequence of the Taliban’s calculated effort to entrench their extremist worldview across generations.

In sum, the continuation of extremist indoctrination in Afghanistan under the Taliban risks further entrenching the country’s backward slide. However, there remains a critical window of opportunity for counter-efforts. Strategic investments in enlightenment, civic engagement, and education reform are urgently needed. Civil society organizations, media outlets, educators, and activists have a historic responsibility to challenge extremist narratives and advocate for pluralism, tolerance, and critical thinking.

The future of Afghanistan hinges on whether the current cycle of radicalism can be disrupted—and whether the voices calling for moderation and progress can find space to thrive.