Almost five decades of instability, foreign interference, and internal conflicts culminated in what many considered unthinkable: the collapse of the Afghan government in 2021 and the Taliban’s return to power. For much of the world, this marked a shocking moment. For Afghans, however, it was yet another chapter in a long and painful cycle of imposed regimes, failed interventions, and broken promises. Afghanistan’s contemporary history has been punctuated by moments that echo each other—foreign invasions, ideological experiments, and internal rivalries have shaped not only the state’s institutions but also the psychology of its people. The roots of this prolonged turbulence can be traced back to the Soviet intervention of December 1979, but even before that, the seeds were being sown.

From monarchy to coup: the road to Soviet occupation

In 1973, while King Zahir Shah was in Italy for medical treatment, his cousin and former Prime Minister Mohammad Daoud Khan staged a bloodless coup, abolishing the monarchy and establishing a republic. Daoud’s vision, however, was not without contradiction—his nationalist and modernizing agenda collided with the increasingly radicalized leftist factions, particularly those within the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA). This ideological friction would eventually cost him his life. By 1978, the PDPA launched a military-backed takeover—the Saur Revolution—and began pushing an aggressive modernization campaign that outpaced the gradual reforms of previous monarchs like Zahir Shah and Amanullah Khan. While these communists imagined a modern state, they failed to read the deeper socio-religious fabric of Afghan society. Land reforms, secular education, and radical restructuring triggered resentment, particularly in rural Afghanistan. What the PDPA framed as progress, many Afghans saw as an assault on tradition. This internal unrest provided a convenient opportunity for external actors to shape the emerging conflict to their advantage.

Afghan refugees cross into Pakistan near Peshawar to escape fighting, May 1980. AP photo

The Cold War’s Afghan theatre: faith vs. communism

The Soviet Union, seeking to preserve its ideological foothold, invaded in 1979 to prop up the faltering PDPA regime. The United States, still licking its wounds from Vietnam, opted for a proxy war, pouring weapons and resources into an emerging resistance force—the Mujahideen. But this was more than a geopolitical chess match. The U.S. deliberately framed its support not just in strategic terms, but also in religious and civilizational language. Zbigniew Brzezinski, then National Security Advisor to President Carter, met with Mujahideen representatives and famously declared:

“We are aware of your deep faith in God and are confident that your struggle will be successful… your cause is just and God is on your side.”

This statement was not simply a diplomatic gesture—it symbolized the fusion of U.S. anti-communism with the Mujahideen’s religious fervor. It was the beginning of what would later haunt the West: the instrumentalization of jihad as a counter-ideology to communism. In that moment, few in Washington foresaw that these very networks would evolve into transnational militant groups, with agendas far beyond the Afghan battlefield.

Soviet troops mobilize in Afghanistan, mid-1980s. Georgi Nadezhdin/AFP/Getty Images

The shadow of proxy politics: From Karmal to Najibullah

The appointment of Babrak Karmal in 1980 as Afghanistan’s Soviet-backed ruler was a clear indication that Afghanistan had become an active battleground in the Cold War’s global theatre. With the ousting and execution of Hafizullah Amin—viewed by some as a rogue element or even a Western asset—Moscow opted for a more loyal and controlled figure to secure its foothold. But loyalty did not translate into legitimacy. Karmal, though more charismatic and polished than his predecessors, was never able to win over the Afghan public. Even with the full might of the Soviet Red Army behind him, his government was simultaneously being challenged by three forces: the Western bloc, the Islamist factions, and at times even disillusioned elements within the Eastern bloc. His failure to quell the insurgency reflected the deep disconnect between Marxist reforms and Afghan realities. Soviet-style modernization plans—often imported wholesale—clashed with Afghanistan’s tribal, religious, and rural structures. The United States, Saudi Arabia, and Pakistan, meanwhile, were not passive observers. They exploited the chaos, transforming Afghanistan into a proving ground for proxy warfare. U.S. support through the CIA, and Saudi money funneled through Pakistan’s ISI, turned the Mujahideen into an ideologically driven military force. Weapons like Stinger missiles, introduced in 1986, shifted the balance of power by neutralizing Soviet air superiority. But the far more enduring export was ideological: jihadist legitimacy framed as a global resistance to communism. In 1983, President Ronald Reagan publicly embraced the Mujahideen in the White House, calling them the “moral equivalent of America’s founding fathers.” This move may have resonated with Cold War ideals, but in hindsight, it blurred the lines between resistance and extremism. Among the foreign fighters who joined the Mujahideen during this period was a then little-known figure—Osama bin Laden. What began as a Cold War alliance would, within two decades, reshape global security and terrorism as we know it.

President Reagan meets Afghan resistance leaders to discuss Soviet atrocities, including the 1982 Lowgar massacre of 105 villagers. Ronald Reagan Presidential Library

Najibullah: the last attempt at a centralized modern state

The fall of Karmal gave way to Dr. Mohammad Najibullah, a figure as complex as he was controversial. A staunch communist and an intelligence chief with a brutal reputation, Najib would become both “The Butcher of Kabul” and—ironically—one of the last leaders to articulate a cohesive vision for a unified Afghan state. Najib’s tenure as head of KHAD (the Afghan intelligence agency) was marked by torture, extrajudicial killings, and political repression. Places like Pol-e-Charkhi’s Polygon became synonymous with state brutality. His tactics earned him infamy, but what is often missed in surface-level critiques is his simultaneous campaign against corruption, nepotism, and rising religious extremism. Najib understood the existential threat posed by the Pakistan-backed insurgents and attempted to resist through both military force and state-building. His project for “National Reconciliation”—launched later in his presidency—was perhaps the most genuine attempt to unify Afghanistan’s fragmented political landscape. But by then, it was too late. The Mujahideen were no longer just rebels; they were victors-in-waiting, empowered by foreign sponsors and too ideologically committed to accept a negotiated peace. Najibullah also recognized a truth few wanted to hear: that Afghanistan could not survive without a strong central government. His calls for national unity, echoed in the tradition of modern state formation seen in countries like Iran under Reza Shah or Turkey under Atatürk, were attempts to reverse decades of tribal fragmentation and foreign manipulation. But Afghanistan lacked the preconditions for success—institutional cohesion, economic self-reliance, and a loyal national army. More critically, it lacked the political space to resolve power through negotiation rather than violence.

A nation without a center

By 1987, Afghanistan had experienced four coups in just over a decade. These frequent and militarized transfers of power revealed the fragility of the Afghan state. With no functioning civil society, and democratic institutions virtually non-existent, power revolved around personalities, factions, and foreign influence—not public mandate or constitutional process. What emerged from this period was a country whose sovereignty was a fiction and whose citizens were left trapped between foreign agendas and domestic fragmentation. The seeds planted in this era—extremism legitimized by foreign powers, militarized politics, and ethnicized governance—would bloom into the conflicts that haunt Afghanistan to this day. Even today, when analysts look back to the collapse of the Republic in 2021 and the Taliban’s return, we must not forget that these were not sudden developments, but the latest cycle in a much longer continuum, born in part from decisions made in the 1980s. Afghanistan’s struggle is not just one of conflict but of identity: Who gets to define the nation—and for whom?

Geneva accords and the illusion of peace: 1988–1989

The Geneva Peace Accords, signed in April 1988 between Afghanistan, the Soviet Union, the United States, and Pakistan, were presented as a diplomatic breakthrough. The agreements formalized the Soviet withdrawal, which was completed by February 15, 1989, marking the end of a decade-long occupation. For many international observers, it was a symbolic end to Cold War tensions in the region. But for Afghans, it was merely the beginning of a deeper fragmentation. While Dr. Najibullah’s “National Reconciliation” policy showed ambition in trying to unify ethnic, political, and religious factions under one national identity, the forces working against him—both internal and external—were far more determined. The mujahideen, fragmented yet militarized, had become dependent on foreign patrons, including Pakistan and Saudi Arabia. For them, reconciliation was not a political compromise—it was defeat. Najibullah’s government, though isolated, remained resilient after the Soviet exit. This was a missed opportunity for dialogue, especially since his warnings about the consequences of uncoordinated power transfers would prove prophetic. His statement—“If power is not transferred to a government accepted by all Afghans, there will be a bloodbath”—was not merely rhetorical. It was a clear-eyed assessment of the fragmented political terrain, which the world chose to ignore.

A Soviet convoy heads toward the border near Hayratan on February 7, 1989, withdrawing from Kabul as part of the Soviet pullout. AP Photo

The post-Soviet vacuum and descent into civil war

After the collapse of the USSR in 1991, Najib’s regime lost its final pillar of external support. By 1992, he attempted to flee, but was blocked by General Dostum’s forces and sought refuge at the UN compound in Kabul, where he would remain until his brutal execution in 1996. The Mujahideen factions, emboldened by victory and unrestrained by a shared vision, entered Kabul and soon turned their weapons on one another. What followed was not liberation, but a devastating civil war. The capital, which had largely survived the Soviet years intact, was reduced to ruins. Over 50,000 civilians were killed in Kabul alone. Cultural landmarks were looted and destroyed, and the very notion of an Afghan nation-state deteriorated. The rise of Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, a man armed by the West and Pakistan, accelerated Kabul’s destruction. His bombardment of the city demonstrated that the new post-communist era would be defined not by democracy or peace—but by militia politics, ethnic rivalries, and foreign interference.

Enter the Taliban: from margins to power

Amid this chaos, the Taliban emerged from Kandahar, composed largely of students from Afghan and Pakistani madrassas, many of whom had been Mujahideen foot soldiers. They promised order and justice—and quickly gained support in a war-weary population desperate for stability. By 1996, the Taliban seized Kabul and began implementing an extreme interpretation of Sharia law. Their brutality was not just physical but symbolic:

They executed Najibullah and his brother in a grotesque public display, hanging their bodies at Ariana Square. It was the Taliban’s way of announcing the death of the Republic and the arrival of a new theocratic regime. But what is often overlooked is that this “new order” was not organically Afghan. The Taliban were heavily shaped, armed, and advised by the Pakistani establishment. They were foreign-backed groups disguised as domestic saviors, and their rise marked not just a shift in power, but the start of Afghanistan’s isolation from the modern international community.

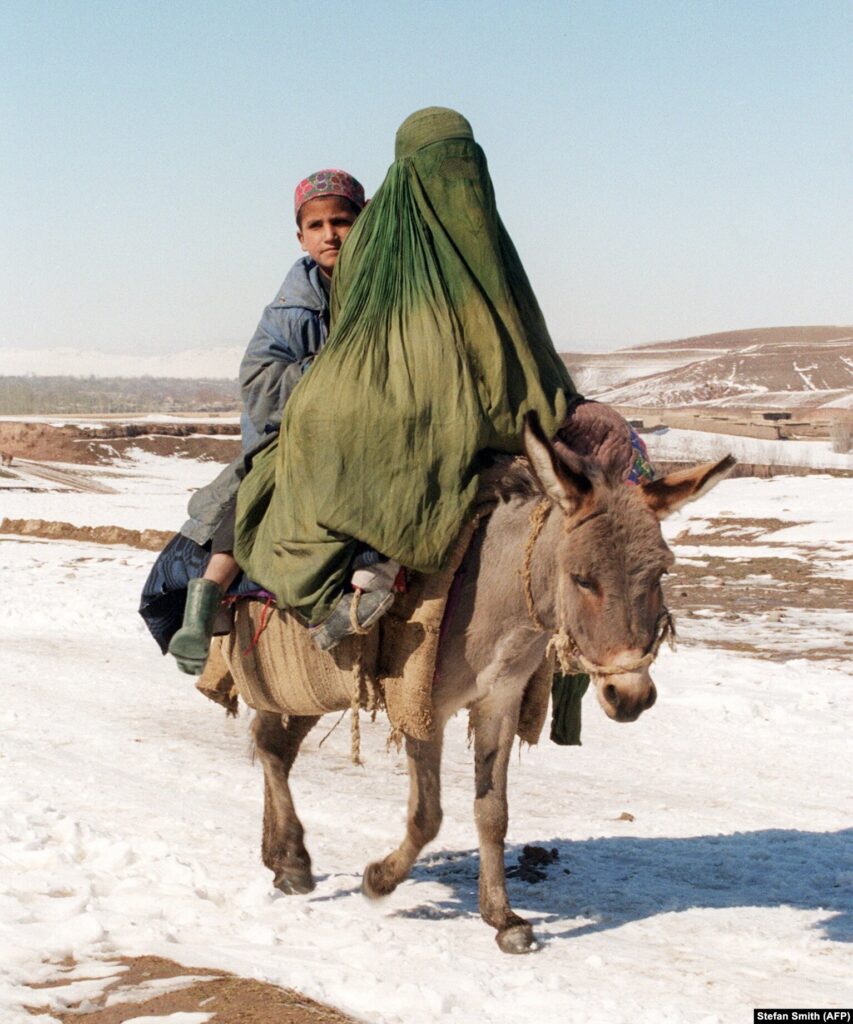

A veiled woman rides a donkey with a young boy. Under Taliban rule, women had to wear full coverings and could only go out with a male relative.

The pre-9/11 era: state terror and global indifference

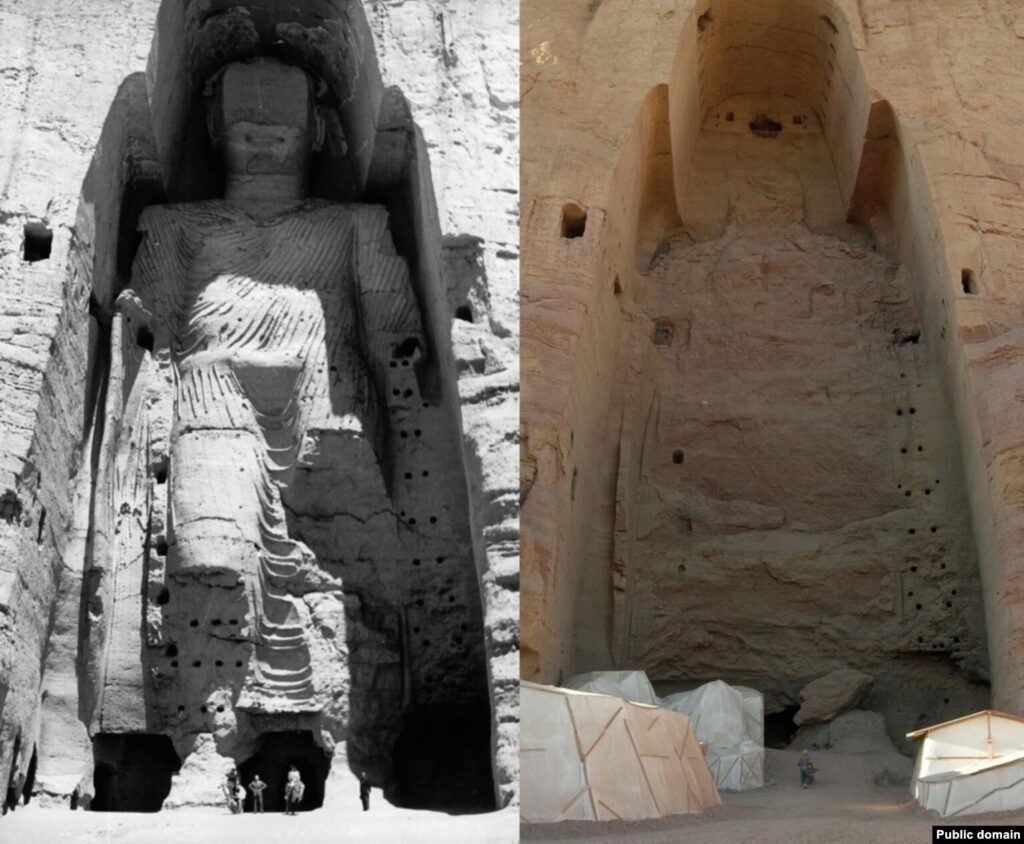

Between 1996 and 2001, the Taliban regime solidified its control. Girls were barred from school. Women disappeared from public life. Public executions, floggings, and amputations became routine. Afghanistan transformed into a sanctuary for global jihadists. Only three countries—Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE—recognized the Taliban government. This selective recognition reflected geopolitical calculations, not legitimate diplomacy. In 1998, the U.S. launched missile strikes on Khost in retaliation for al-Qaeda’s bombings of American embassies in Kenya and Tanzania. But these attacks did little to disrupt the deepening ties between the Taliban and global jihadist networks. The international community, including the UN, imposed sanctions in 1999, and yet the Taliban remained defiant. Their decision to destroy the Buddhas of Bamiyan in 2001, despite international pleas, revealed a regime not just intolerant of modernity—but actively hostile to cultural heritage and pluralism.

They weren’t just ruling Afghanistan—they were redefining it in narrow, exclusionary, and militant terms.

Before-and-after images of the giant Bamiyan Buddha, destroyed by the Taliban in 2001 for religious reasons, citing a fight against idolatry.

Taliban fighters prepare to pray at Kabul’s Arg Palace in autumn 1996, shortly after seizing the city from warring mujahedin factions.

Massoud’s assassination and the final countdown to 9/11

In the midst of this, Ahmad Shah Massoud, the leader of the Northern Alliance, was one of the few remaining anti-Taliban figures with national stature. On September 9, 2001, just two days before the 9/11 attacks, al-Qaeda operatives assassinated Massoud in a suicide bombing disguised as a media interview. His death cleared the way for al-Qaeda and the Taliban to tighten their grip—and removed one of the few credible Afghan voices who could have united the country in opposition to extremism.

From Afghan crisis to global catastrophe: 9/11 and the U.S. response

September 11, 2001, redefined the world’s relationship with Afghanistan. Al-Qaeda’s attacks on the U.S. revealed the cost of years of strategic neglect, short-term alliances, and ideological outsourcing. The Taliban’s refusal to hand over Osama bin Laden led to the launch of Operation Enduring Freedom on October 7, 2001. Within weeks, the Taliban regime collapsed. The Northern Alliance, now supported by U.S. air power and special forces, took Kabul. A new interim government was formed under Hamid Karzai after the Bonn Agreement. But the new government was flawed from inception. Many of those placed in power were warlords with bloody pasts, once again returning to state positions—not because of legitimacy, but because of expediency. This paved the way for a cycle that would repeat itself: temporary stability built on fragile foundations.

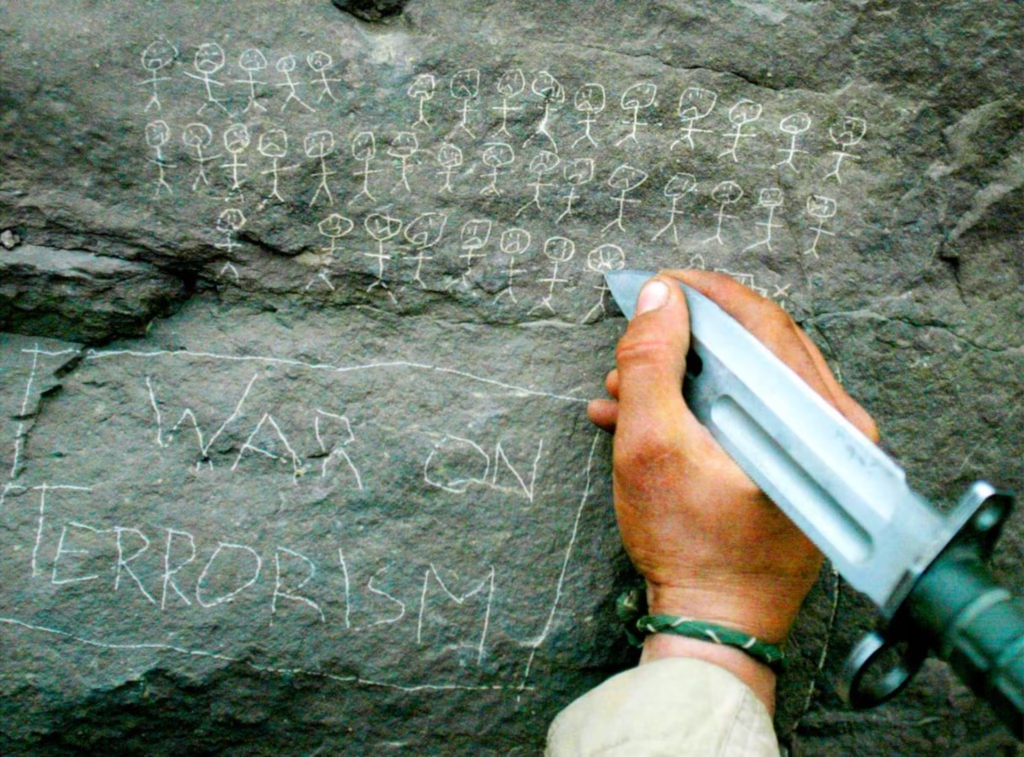

A U.S. soldier from the 10th Mountain Division marks their mortar team’s body count on a rock near Sherkhankheyl, Marzak, and Bobelkiel, March 9, 2002. REUTERS/POOL/Joe Raedle

The illusion of democracy and the resurgence of shadows (2004–2021)

The 2004 presidential elections were celebrated internationally as a milestone in Afghanistan’s democratic journey. Hamid Karzai, once seen as a unifying figure with international backing, transitioned from interim president to an elected leader. But beneath the surface, the cracks were already forming. By 2005, when parliament reopened, it was filled not with representatives of reform or the people—but with warlords, faction leaders, and power brokers returning to Kabul in new suits under old identities. What was framed as democratization was in reality a re-legitimization of militia-era power through ballots instead of bullets. The very individuals who had once torn the country apart were now given official portfolios and protection, setting the stage for elite-driven politics detached from the Afghan people.

The return of the Taliban and NATO’s strategic paralysis (2006–2014)

By 2006, the Taliban had already begun reclaiming territory in the south. The belief that the war had been won was proven premature. NATO’s ISAF took over from the U.S. in southern Afghanistan, and what followed was described by NATO officials themselves as one of the most challenging missions in the alliance’s history. While the West scrambled for strategies, the Taliban embedded themselves in rural networks, exploited grievances, and re-emerged not just as a military force but a propaganda machine. In response, troop numbers surged—particularly under President Obama, who also vowed a 2011 withdrawal. In reality, however, the Obama-era surge deepened Afghanistan’s dependence on foreign troops without resolving underlying political, governance, or legitimacy crises. By 2013, Afghan forces formally took over security operations. Yet this transfer was largely symbolic. Without stable institutions or trust in government, the national forces struggled to hold ground, even as the Obama administration signaled the beginning of peace overtures with the Taliban.

A young amputee walks through Kabul’s Eidgah Mosque on December 8, 2001, as the UN World Food Programme begins its largest food distribution, aiding most of the war-hit city’s population. REUTERS/Peter Andrews

Transitions and the rise of political paralysis (2014–2019)

The 2014 presidential election turned into another crisis. Ashraf Ghani’s narrow victory over Dr. Abdullah Abdullah triggered accusations of fraud and ethnic polarization.

The intervention by General Petraeus and the creation of a “Chief Executive Officer” post for Abdullah was not a solution but a political bandage—a recognition that Afghanistan’s democratic institutions could not resolve conflict without foreign arbitration. During this period, the Taliban gained ground not just through arms, but by offering an alternative to corrupt governance in many rural areas. Despite NATO’s Resolute Support Mission, Afghan morale declined, and the Taliban accelerated attacks against civilians, journalists, and U.S. targets. Peace talks in Qatar resumed, but they were hamstrung by fragmentation on both sides—and by the fact that the Taliban had no incentive to compromise while it was winning. In the midst of these negotiations, the group announced the death of Mullah Omar, revealing he had been dead for years. His successor, Mullah Akhtar Mansour, was swiftly killed by a U.S. drone strike in Pakistan, exposing once again the cross-border sanctuaries that had fueled the insurgency for decades.

U.S. troops search for Taliban fighters in the mountains near Kandahar in 2003, after many had retreated or fled to Pakistan.

From the butcher to the negotiator: Hekmatyar’s return (2016)

In an astonishing turn, the Afghan government granted asylum to Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, the man once labeled the “Butcher of Kabul” for his role in the city’s destruction during the civil war. This move was presented as a step toward peace, but to many Afghans, it symbolized the moral bankruptcy of the political process—where war criminals were repackaged as peacebuilders for the sake of optics.

Trump, Khalilzad, and the road to Doha (2018–2020)

With Donald Trump’s rise to power came a shift: Zalmay Khalilzad, a familiar Afghan-American figure, was appointed to negotiate directly with the Taliban.

Afghan officials were largely sidelined in this process, as the U.S. prioritized troop withdrawal over a sustainable peace. The February 2020 Doha Agreement offered the Taliban international legitimacy in exchange for vague promises to reduce violence and avoid harboring terrorists. Crucially, the Afghan government was not a signatory. This omission revealed the extent to which Kabul had lost both relevance and sovereignty in its own affairs.

Zalmay Khalilzad, U.S. Special Representative for Afghan Reconciliation, and Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar, one of the co-founders of the Taliban, after signing the U.S.-Taliban peace agreement in Doha, Qatar, on February 29, 2020.

The final collapse (2020–2021)

While Ashraf Ghani remained president after another disputed election in 2019, power had already begun slipping. ISIS-K attacks in Kabul targeted hospitals, schools, and human rights defenders, and the government’s response was inadequate and inconsistent. Violence, fear, and mistrust deepened. When Joe Biden announced on April 14, 2021, that U.S. troops would withdraw by September 11, the stage was set. By May, the Taliban began retaking territory. By July, U.S. forces had abandoned Bagram Airbase. By August, most provinces fell to the Taliban without resistance, not due to military superiority, but because the state had already hollowed out from within. Ashraf Ghani fled on August 15. The Taliban walked into Kabul. The republic fell, not with a fight, but with a whisper. At Kabul Airport, desperation turned into chaos. On August 26, a suicide bombing by ISIS-K killed nearly 200 Afghans and 13 U.S. service members. By August 30, the last U.S. plane departed. The Taliban declared “complete independence.” But for ordinary Afghans, this was not liberation—it was abandonment.

The Taliban take control of the Presidential Palace of Afghanistan, August 15, 2021.

The bitter legacy and the fight for the future

The Taliban now governs a broken country with no roadmap for legitimacy, no plan for development, and a deeply fractured society. Their promises of inclusion, rights, and moderation remain unfulfilled, as the space for civil liberties narrows by the day. Afghanistan’s long and complicated journey toward modernity—one that began under Amanullah Khan, flourished briefly in the 1960s and 70s, and was derailed by foreign-sponsored jihad and repeated militarization—has once again been delayed, if not reversed. Islamist fundamentalists, once unable to seize power due to lack of resources, were empowered in the 1980s by Western money, Saudi ideology, Pakistani infrastructure, and later, strategic neglect. What we face today is not just a humanitarian crisis—it’s the product of decades of outsourced security, compromised leadership, and a global system that prefers short-term exit strategies over long-term state-building. The question now is no longer how Afghanistan fell. The question is: What will be done—if anything—to ensure it rises again?